Photo: Berenice Zambrano / Carlos Enciso

A couple of years ago, on my way back to Mexico, I stopped for a few days in Antigua, Guatemala. One morning, at the hostel where I was staying, I was brushing my teeth. Next to me, a white man came to wash his hands and face; he turned on the tap, let the water run while checking on his eye bags and beard. A few seconds passed, and I knew he wouldn’t turn off the tap. He continued with his personal care routine, and I finished brushing my teeth. The water kept running. About 25-30 seconds had passed. So I asked him:

— Do you really need all that water to keep running?

I immediately noticed that he wasn’t used to be questioned. Without turning to me, he repeated my question slowly to himself:

— Do I really need all that water to keep running?

Then, his brain connected the dots and turned off the tap right away.

— Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t notice

— It’s okay, thank you. I grew up without access to water, and seeing how it’s wasted, makes me feel very sad.

— No, you’re right.

— btw my name is Luis, see you around.

— Matt, see you.

Although it was all very friendly, I could feel both of us inside showing antipathy for each other and handling the situation in the most civilized way. I left the bathroom to start my day and never saw him again.

I grew up in Iztapalapa, the most densely populated municipality in Mexico City, probably in Mexico and in the top 5 in the Americas. It’s also one of the places with the highest density of Covid-19 infections in Mexico. For me and my family, who lived in a poor/middle-class neighborhood, water cuts were part of our lives; we developed habits such as taking baths in jicarazos, collecting rainwater, having a tray in the sink to reuse water. That reality made us aware of the value of water.

When I lived in Seattle, I noticed that people did the same thing in the public bathrooms and in my friends’ homes. When I asked them if they weren’t worried about the water being wasted, they always had a shocking reaction; it was genuinely the first time that an outside agent had questioned them. The confusion on their faces was the same.

The Water Issue

I believe that problems like water should be solved structurally, from the root. However, it’s important to mention that the conditions for structures to work and, even more so, for them to be equal, do not always exist.

Even though I grew up in a fairly hostile environment, in terms of water, we had access to it, it was scarce, though. We owe it to my mother, who educated us to treat our water frugally. At school, the local government made brigades about saving and caring for water, and my mother’s teachings made me a cautious person about water. So, in ideal scenarios, I think that good education and global contextualization can help people have a more respectful relationship with the use of such a valuable resource.

Currently, 1 in 3 people in the world, or more than 2.6 billion people don’t have access to safe drinking water. That number is so large, it can easily lose its value. That number of people is similar to the total population of China and India (2,800,000,000 people). Another reference would be the total population of Europe 3 times. That is 3 Europes without access to drinking water.

What are the structures that have caused this global problem of access to water? The next question we have to ask ourselves is: Where is this lack of access to water distributed? According to the organization water.org+ this problem is concentrated in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. What do these 3 continents/regions have in common?

Colonialism

Talking about colonialism is complicated, I personally see it as a hydra of many heads. Many people and territories have suffered its consequences for centuries. Many people and territories have benefited from it for centuries. In the end, it depends on who tells the story and for what purpose.

The largest empire in history, the Mongolian one, since the 1200s had already consolidated, thanks to its expansive practices, colonialism. Later, the Egyptian, Roman, and Greek empires, among others, expanded by creating colonies in places they conquered through violent invasions where we know today as Africa and Europe. The most recent intrusions took place since the 15th century with European countries, colonizing Africa, Asia, and America.

The principle has been the same, to expand economic power by subjugating others, expanding the property by taking other civilizations’ property by force and erasing them, either by destroying their knowledge and making them assimilate their own or by killing them.

For the expansion to happen, it’s necessary to send the armies and scouts first. Once the territory has been conquered, it will be necessary to populate the new region and send people to live in the new land.

Before we get to the point, let’s rewind for a moment. What does the word conquered imply? Without beating around the bushes, it’s taking away from someone else what belongs to them. It’s not asking for it or negotiating it.

Resources

One of the main engines that have helped colonization work for centuries is the natural resources of the conquered lands. In commercial terms, get resources for free or at very low cost and then use them or market them at a higher price, is a very prolific business.

The colonialist processes do not end once the intrusion is over. That’s just the beginning. Then comes the transition to start with the extraction of resources and wealth. In the case of the American continent, it happened for more than 3 centuries. Until the independence of the colonies made them independent countries. But it was not the people of the original families who conducted those movements.

The inhabitants of the original territory and their descendants were left with few options. Either annihilated or diminished under the illusion of a mestizaje that has been slowly erasing them for centuries.

The independence of the colonies or colonized territories was initiated and consummated by people descending from colonizers and mestizxs. It was only a division of power/territory/property/resources between those who have had it since the invasion was consummated.

Over the years, these new nations have continued to be targeted for resource extraction. Colonization has changed its shape. With the arrival of modernity born from the industrial revolution, the dominance of the economy and the possession of the territory is no longer defined only by who is physically occupying it. But by loans, debts, treaties and commercial agreements that define the dynamics of power.++

The resources are limited -not insufficient-. In this new modality of financial control, regulation of the extraction, and possession of wealth, there is one more column that supports this balance. Who decides how resources are managed?

Neocolonialism

At some point in history, that power was no longer concentrated in governments, but in those who accumulate wealth on a large scale; corporations. Through lobbying and their economic power, they can even control the course of elections around the world (Odebrecht+++) or obtain water concessions (Nestlé^) or mining^^ (Tesla, Apple, Samsung, etc.).

This collaboration between state and corporations has become a political entity hard to regulate. As judge and party, it is very easy for decisions with particular interests to be made through legal channels. Sometimes, thanks to activism and journalism, this type of practice can come to light, although there isn’t always a consequence. Who watches the watchmen? They say.

It's essential to understand how this dispossession has worked historically; how we have benefited from it, but more importantly, to learn about it to avoid perpetuating it. It is crucial to understand and assume that this dispossession and systems exist.

Even with documentary evidence of the extraction that has occurred for centuries§, the official discourse will always be narrated by the hegemonic system^^^. When an opinion or research that offers a different version is alternative by nature. It tends to be questioned and minimized by the same system. It’s precisely in colonized territories or where there are conflicts over resources, where being a journalist is a profession that costs hundreds of people their lives every year. §§

So, what does all this have to do with the encounter with this English backpacker in Guatemala? I hope that this text helps to contextualize why water is not scarce in the same way in countries and regions that economically dominate the world.

The so-called third world (formerly European colonies) continues to be a source of resource extraction to provide these countries (and their descendants in the colonies) with fundamental rights such as clean and safe water because their aquifers are not plundered to be used as a resource so that entire industries (beverages, livestock, agriculture, even drug trafficking, and others) can continue to operate. Batteries for luxury electric cars at the expense of lithium reserves in Bolivia§§§ and Australia. Longer lasting mobile phone batteries at the cost of precarization and exploitation of impoverished communities in the Republic of Congo. Bananas for an entire country at the price of systemic extractivism of countries such as Guatemala, Honduras, and Colombia. The list is longer.

I am sure that we will never see the exploitation of children from London so that a community in southern Mexico can have some basic comfort or service.

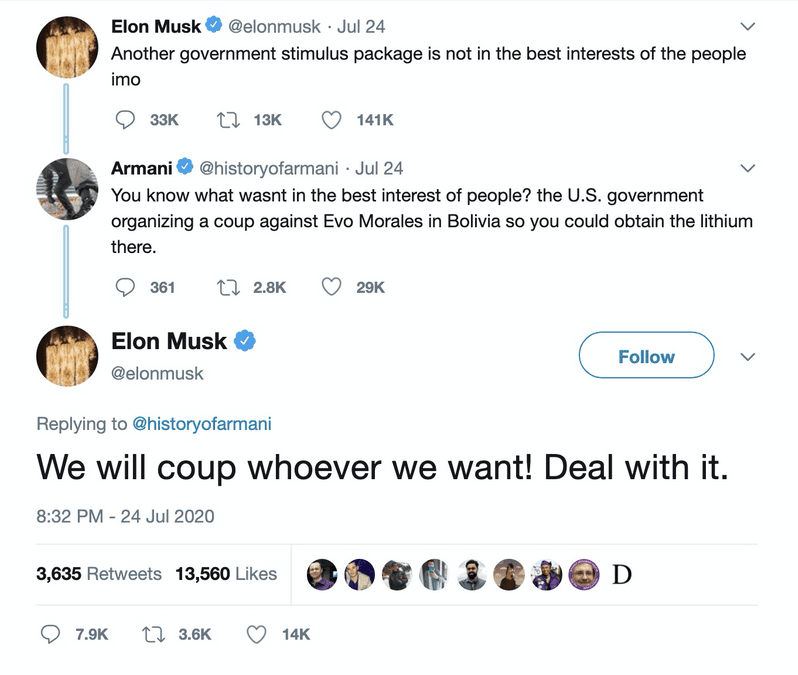

Because of this, I consider important to do this type of critical exercise from our global south; to challenge Matt’s we meet every day, either those who visit and those from here. White men with power and money are used to being in control and having no one questioning their actions. That has to change until it’s normalized; otherwise, men like this will continue to be raised, and their cheekiness will remain the status quo in our societies:

Beneath the Elons and the Matts, many privileged people (me included) have benefited from the colonial system at the expense of people whose rights, territories, or lives have been taken away. Specifically indigenous, black, or racialized people. So it’s also essential to understand how this dispossession has worked historically; how we have benefited from it, but more importantly, to learn about it to avoid perpetuating it. It is crucial to understand and assume that this dispossession and systems exist. It’s a heavy burden that excludes people from access to services such as basic health, education, or technology; to include others.

Some ideas to help counteract these structures is to support alternative content creators, look out for projects born from the black or indigenous community, buy them directly and without intermediaries. Question projects that use word empowerment, or give voice from a white or mestizo privilege. Look for people who write about these issues from their perspective. Question the government and institutions that continue their projects of nationhood that include erasing or making this sector of the population invisible for years.

It’s essential to read about history with a critical attitude because the official history is part of that system, which I’m talking about in this text. As that phrase says, history will always be written by the winners (and the colonizers). Here are some recommended readings that have personally helped me to learn and modify my behavior and to think about these problematic issues (In Spanish).

Sources and Notes

++ Kicking Away the Ladder. Ha-Joon Chang. You can buy the book here.

^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6WbHGfjpYM y https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CPIEaM0on70

^^^ https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hegemon%C3%ADa_cultural

§ When Banana Ruled. Mathilde Damoisel. (In Spanish) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0R8AVcB6Aic). Info (http://icarusfilms.com/if-banana)

§§ https://thestacker.com/stories/3429/most-dangerous-countries-journalists